Be a Character. Dress Like That.

Fred Castleberry, Wes Anderson, Scott Fitzgerald, and Ethan Wong believe in complex characters. You should be one.

Wes Anderson is an auteur. He doesn't just write or direct a film. He digs deep into the details, and it shows through every aspect of the film's style. He uses head-on profile shots, rich color schemes, and symmetry. His characters are deep, complex, fun flawed, and wonderful.

But film is not the longest form of media out there. A novel or television show gives you time to really develop a character, but if you want to do that in film, you have to say a lot in a short span of time. So the visuals have to inform the depth of the character. The profile shots allow us to focus on one character at a time. But look at the way they dress!

Anderson's rich, distinct characters have rich, distinct uniforms, which each speak volumes about them. Fred Castleberry and Ethan Wong both take that perspective to their photography and the way they style an outfit. In this article, I'll make the case that you should too. I'll go over Anderson's approach in further depth, as well as the approaches of several writers. But first...

Fred Castleberry and the Rogue's Gallery

Fred Castleberry loves Wes Anderson. In a recent episode of HandCut Radio, Fred describes how Anderson inspired him to develop characters for his eponymous brand's lookbooks.

His brand is primarily made-to-measure, which presents something of a problem: without readymade clothing to place on models, how does he market his aesthetic? He could make them some custom pieces, sure, but he doesn't have a whole line to start them off with—he has to make each piece for marketing purposes, so he has to make each piece count, and show off his signature aesthetic and his range as a custom maker.

So, having spread the idea that the better you dress, the worse you can behave, he picked an aesthetic and characters to reflect his vibe. His characters would be a rag-tag group of art thieves. The theme is fun, and allows for very visual storytelling through images alone.

The story didn't need to be deep. Just fun and strangely aspirational. You don't want to be a thief, but you want to wear funky tailoring while you run around a vaguely European city getting into all sorts of shenanigans. You want to find yourself running across rooftops, lowering paintings from balconies, driving a getaway car. You want to live more, and his characters can really live in his clothing.

The other details reinforce the aesthetic. The tape player and chunky cell phones help create a time frame. Art itself reflects luxury. The car, carriage, tape player, pizza, and beer all show what the characters enjoy outside of their work and their attire.

FE Castleberry reflects this in their accessories. They sell ashtrays stolen from hotels. Their cashmere beanies are burglar caps. They sell vintage monogrammed briefcases and ridiculous desk plates.

Think about your aesthetic. What do you think is fun? Is it reflected in the way you dress? Do you seem like the kind of person you want to be? Is your clothing conducive to what you aspire to—the adventures you want to lead, the people you want to be around?

If not—why not? They can engage in heists, drink pizza, and eat beer in suits. What's stopping you from living in the clothes you love? Are they the wrong clothes, or are you just not letting them see their true potential?

For what it's worth, many large fashion houses take a similar approach, including, for example, Gucci, as in the video below.

The Royal Tenenbaums

The characters of The Royal Tenenbaums, written by Anderson and Owen Wilson, are reflected beautifully in the work of Karen Patch, costume designer, and Eric Anderson, illustrator for the film.

They designed a family in decline, a family that established a style in its past success and current depression, as described in this interview with Entertainment Weekly. Traditional suits, a fur coat... luxury from the past. The attire of each child bears some relation to tennis, even though only one of them is a tennis prodigy.

While all the costumes functon to deeply represent the characters wearing them, I will focus specifically on the five Tenenbaum men—Royal, Richie, Chas, Ari, and Uzi.

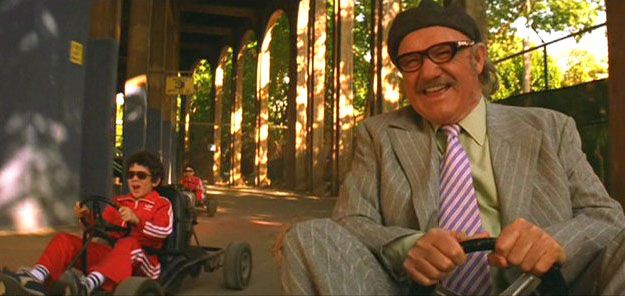

Royal

Royal is a scoundrel. He's dishonest and lazy. He has a favorite child, and it's not the son he shot or the doctor he always introduces as adopted. He's often shown smoking, even though he's supposedly dying of cancer. Smoking is just one of the awful traits he's passed on.

His suit is a very traditional gray-on-gray pinstripe double breasted. It's a 6x3, an unusual button arrangement with a tall vertical row, and has smallish horizontal peak lapels. It doesn't fit him especially well anymore, if it ever did. He wears ties and colored shirts, consistent with what you might expect of a man who got into tailoring young and just never changed.

Not only does this reflect past wealth, it helps code him as a grandfather. His attire is stale vintage. His tweed overcoat is something only old men wear. He has been living in a hotel for some time now, perhaps in stasis. He hasn't changed, and he certainly hasn't had spare cash for new clothing.

But when he gets kicked out of the hotel, Royal wants to move back into his family home. Maybe at first, he just wants to guilt them into giving him a place to stay. He lies about his cancer, and Chas doesn't trust that he has any good intent at all.

But then he starts spending time with his family, and things change.

Particularly, Royal sees Chas in pain, and sees Ari and Uzi's childhood passing them by. The old rule that parents are responsible and grandparents are fun comes shining through. Royal takes his grandchildren not only go-carting, but gambling. They play tennis. They have fun. And in that process, for what might be the first time, Royal actually starts to love his family.

Royal sees happiness, still in his old suit. He moves in it, sometimes forgetting to unbutton the jacket when he sits down. He throws on a beret. He doesn't really change his style much, but the clothing looks better the more he relaxes.

At the climax of the film, Royal saves Ari and Uzi from Eli's car crash, finally earning a chance to repair his relationship with Chas. By the end, he's repaired his relationship with his whole family, redeeming himself.

Richie

Chas wears a track suit and Margot wears a polo dress, but Richie is the athlete of the bunch. A tennis prodigy, he wears a headband and a tennis polo. Athleisure seems to represent their generation, but Richie's costume doesn't stop there.

He wears a camel hair suit with jetted pockets and pointedly too-short sleeves, perhaps another sign that none of the family's clothing is new. This mixture, this casual tailoring, was an incredible precursor to the menswear merger. More importantly, the suit is a reference to his father's old-fashioned attire; as his favorite, Richie spent no shortage of time with Royal.

Finally, Richie wears a large pair of aviator sunglasses. This, along with his beard and long hair, shows us that Richie is hiding. What's he hiding from?

Well simply, Richie is in love with Margot, and has been suffering from depression since he found out that she got married to Raleigh. Moreover, Richie's best friend Eli is also in love with Margot (and undergoing a breakdown of his own). Perhaps he's hiding from the world, in depression, or perhaps he's hiding from Margot, to whom he cannot express his feelings.

At his own personal climax, Richie takes off his sunglasses, shaves his head, shaves his beard, and slashes his wrists.

Richie survives, and the first thing he does upon escaping the hospital is profess his love for his sister. She feels the same. He's done hiding, he took a chance, and it worked out.

Richie loses the headband and the sunglasses. The suit he wears to his mother's wedding is a gray single-breasted peak-lapelled three piece. He wears a yellow and gray striped tie and a white shirt. He spends time with his bird, Mordecai, on the roof, and shares a cigarette with Margot.

Chas, Ari and Uzi

Chas wears ond of the simplest and most iconic outfits in all of film history—distinct from the tailoring worn by most of the cast, but nearly identical to his sons' outfits.

Unlike his brother, the Tennis star, Chas is not, primarily, an athlete. Rather, he is a whiz at business and math. Nevertheless, he almost exclusively wears Addidas track suits, and almost exclusively this bright red one. On a superficial level, the bright red athleisure symbolizes that Chas is angry at his father, and that he is never at rest, constantly in motion, working, caring for his children, or distracting himself from his troubles. But the track suits symbolize so much more.

Chas wore suits when he was younger—perhaps inspired by his father. He is one of the only characters who grew up to change his day-to-day style. Is this representative of his personal financial success, or of what he lost?

The track suits reflect Chas's isolation, and his especially distant relationship with his father. Where Royal wears, arguably, the most traditional suits in the film, Chas separates himself from the remainder of the cast by wearing a track suit. Richie and Royal wear traditional wool suits with lapels. Henry wears a blazer and bow tie. Raleigh wears a blazer. Pagoda and Eli wear dress pants and button ups. But Chas and his sons wear pure athleisure, wear bright red track suits with sneakers. This is not only reflected in his outfit and the writing, but in the framing of many iconic shots in the film. Chas separates himself from others.

Well, not all others. Chas separates himself from the world, but pulls two characters closer by dressing them precisely like himself. Ari and Uzi, without their mother, are like clones of their father, who controls their every move, down to the way they dress, and raises them to be like him. He isolates his sons, who he loves, from the rest of his family. And he is overprotective because he's faced loss, and cannot bear the thought of losing the only family he still has any relationship with.

The track suits further seem to represent Chas's immaturity—he wears what young men might wear, what his sons wear—and Ari and Uzi's lack of a childhood—they wear what young men might wear, what their father wears. All three are in a state of arrested development, and only one man can break them out.

Chas's arc is Royal's arc. Chas closes himself off from his family, and particularly from forgiving Royal, effectively punishing his children in the process, depriving them of a childhood. Chas may not be a scoundrel, but his father provides much needed balance and connection to Ari and Uzi's lives. He gives them the childhood that Chas could never give them, the childhood that Royal could never give Chas.

Anderson, Anderson, Wilson, and Patch designed the Tenenbaum family perfectly to reflect who they are, and the plot of the film on a deep level. And that brings me to my point. I urge you to design your own personal aesthetic to reflect who you are with the same level of care and effort. But I'm not the first to make this point.

On "Cinematic" Dressing

Ethan M. Wong made a point similar to mine in his article, "On Cinematic Dressing." I ultimately think his article confusses several ideas—the idea of dressing like a character, but also the idea of dressing like you're in a movie, or the main character of the movie, or dressing with flair. I want to sift out the first idea from the rest.

Movies are not costumed solely to represent the characters as well as possible. Movies are designed for practical reasons: mass market appeal, sex appeal, attention-grabbing flair, and product placement among them.

James Bond and his skinny suits are really an example of all of these motivations. Ethan mentions the flair, but the character is constantly used to market clothing to us. His suits fit poorly. Jany Temime has told us why they fit him like that. Craig asked for something slim, and wanted to show off his body, and Temime was happy to help him show off his body. She went to Tom Ford, and Tom Ford agreed to the plan that would make them money. Granted, he doesn't look like he could comfortably move in his suits, or ride a motorcycle. They don't reflect british class or any kind of practical spy purpose. The goal wasn't to reflect his character.

Instead of focusing on film, where costumes are required and serve all of these alternative motivations, I think we can look to other media to understand how we might develop characters. Particularly, I think we can gain some insight from the way characters are developed in literature.

The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby is a novel not only about 1920s culture, but about perception, and self-perception. Nick Carraway is the quintessentially unreliable narrator. His descriptions of clothing are, therefore, suspicious. Nick doesn't tell us what people wear because we need to know, or even really to explain who the characters are. He describes their clothing as a way to signal how he percieves the characters.

For example, his initial description of Tom Buchanan tells us very little about Tom, but a whole lot about Nick:

He had changed since his New Haven years. Now he was a sturdy straw-haired man of thirty, with a rather hard mouth and a supercilious manner. Two shining arrogant eyes had established dominance over his face and gave him the appearance of always leaning aggressively forward. Not even the effeminate swank of his riding clothes could hide the enormous power of that body—he seemed to fill those glistening boots until he strained the top lacing, and you could see a great pack of muscle shifting when his shoulder moved under his thin coat. It was a body capable of enormous leverage—a cruel body.

I must have missed this paragraph when I first read the novel, and assumed Nick was asexual. Nick is not asexual.

Of course, Nick's not interested in his girlfriend, Jordan Baker:

I looked at Miss Baker, wondering what it was she “got done.” I enjoyed looking at her. She was a slender, small-breasted girl, with an erect carriage, which she accentuated by throwing her body backward at the shoulders like a young cadet. Her grey sun-strained eyes looked back at me with polite reciprocal curiosity out of a wan, charming, discontented face. It occurred to me now that I had seen her, or a picture of her, somewhere before.

Notice everything Nick does to get around Jordan's gender. She has small breasts and "shoulders at like a young cadet." He throws in the word "erect." Even Jordan's name is gender-neutral. Nick would struggle to find a more masculine beard.

Nick's description of women in general is disinterested, as we see in Tom's mistress, Myrtle Wilson:

His voice faded off and Tom glanced impatiently around the garage. Then I heard footsteps on a stairs, and in a moment the thickish figure of a woman blocked out the light from the office door. She was in the middle thirties, and faintly stout, but she carried her flesh sensuously as some women can. Her face, above a spotted dress of dark blue crêpe-de-chine, contained no facet or gleam of beauty, but there was an immediately perceptible vitality about her as if the nerves of her body were continually smouldering.

And shortly thereafter:

She had changed her dress to a brown figured muslin, which stretched tight over her rather wide hips as Tom helped her to the platform in New York.

And again -- Nick seems rather focused on the exact fabrics Myrtle wears, perhaps trying to distract himself from her figure:

Mrs. Wilson had changed her costume some time before, and was now attired in an elaborate afternoon dress of cream-coloured chiffon, which gave out a continual rustle as she swept about the room. With the influence of the dress her personality had also undergone a change.

You'll notice the pattern of describing men in feminine terms and women in masculine terms actually continues, importantly, with the McKees.

Mr. McKee was a pale, feminine man from the flat below. He had just shaved, for there was a white spot of lather on his cheekbone, and he was most respectful in his greeting to everyone in the room... His wife was shrill, languid, handsome, and horrible.

In case you missed it, or forgot, or never read The Great Gatsby, Nick slept with Chester McKee—although he never directly tells us that. Is he belittling Lucille to avoid his guilt? Is he calling Chester feminine to avoid his truth?

We could continue talking about Daisy, Owl Eyes, Meyer Wolfsheim, Ewing Klipspringer, or white and yellow, but we still haven't reached Gatsby. So as a quick rundown: Daisy, the East Egg, and the West Egg are white on the outside and yellow on the inside. Yellow is analagous to gold, which represents wealth and excess, and also, perhaps by extension, corruption. White is purity, or the pretense of purity, but also blankness or emptiness.

Jay Gatsby, Himself

Now, the most important and most detailed descriptions are of Gatsby, with whom Nick is in love. Nick, still in denial about his sexuality, can only show us how he feels through his untrustworthy descriptions of the main object of his desire, and can only feel it vicariously through his second cousin.

We hadn’t reached West Egg village before Gatsby began leaving his elegant sentences unfinished and slapping himself indecisively on the knee of his caramel-coloured suit.

Caramel-coloured might imply gold or yellow, or might just be a sign of his vast wardrobe. We see a clearer egg-based color scheme when Gatsby first meets Daisy at Nick's:

The flowers were unnecessary, for at two o’clock a greenhouse arrived from Gatsby’s, with innumerable receptacles to contain it. An hour later the front door opened nervously, and Gatsby in a white flannel suit, silver shirt, and gold-coloured tie, hurried in. He was pale, and there were dark signs of sleeplessness beneath his eyes.

A rare white flannel suit hiding silver and gold. The exact color scheme of the "eggs," and the one closely associated with Daisy herself. Perhaps Nick believes that Gatsby is pure, but Daisy will corrupt her.

Next, we get to see the sheer opulence of Gatsby's wardrobe. We already know that he bought Lucille McKee a $265 gown—roughly $4600 today—after she tore one at one of his parties. How much more must Gatsby spend on his own wardrobe?

Recovering himself in a minute he opened for us two hulking patent cabinets which held his massed suits and dressing-gowns and ties, and his shirts, piled like bricks in stacks a dozen high.

“I’ve got a man in England who buys me clothes. He sends over a selection of things at the beginning of each season, spring and fall.”

He took out a pile of shirts and began throwing them, one by one, before us, shirts of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel, which lost their folds as they fell and covered the table in many-coloured disarray. While we admired he brought more and the soft rich heap mounted higher—shirts with stripes and scrolls and plaids in coral and apple-green and lavender and faint orange, with monograms of indian blue. Suddenly, with a strained sound, Daisy bent her head into the shirts and began to cry stormily.

“They’re such beautiful shirts,” she sobbed, her voice muffled in the thick folds. “It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such—such beautiful shirts before.”

Daisy is no stranger to money, of course. But Gatsby, it is now clear, has a wardrobe like no other. The sheer excess—sheer linen, thick silk, fine flannel in many colors—reflects the greater (overt) theme of excess throughout the novel.

I'm not sure why Daisy cried over the shirts, but there's a good chance she didn't—either that she was lying to cover up the real reason she cried, or that Nick's narration has robbed us of some deeper truth. It's also possible that Daisy is just horribly superficial, or that Nick thinks so, but I doubt that. Remember, Daisy is the one who said of her daughter, in the words of Zelda Fitzgerald, "All right, I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool." This reflects her pain, living in a world she percieves as shallow. Maybe that's why Daisy cries—even Gatsby has given way to beauty.

Later, Tom addresses the claim that Gatsby went to Oxford:

“An Oxford man!” He was incredulous. “Like hell he is! He wears a pink suit.”

Tom says this dirisively. Perhaps this disdain is old money spiting new, perhaps it's masculinity insulting femininity, but it definitely reflects Tom's passive-aggressive anger at the man fucking his wife. Nick has a different perspective on the suit, but we'll see later.

Pink itself might represent the love Gatsby feels for Daisy, but might also represent some degree of femininity or ostentation. For what it's worth, pink suits are baller af. But Tom wouldn't know that.

The pink suit is mentioned again when Gatsby and Nick discuss the car crash that killed Myrtle Wilson:

I must have felt pretty weird by that time, because I could think of nothing except the luminosity of his pink suit under the moon.

And later, still:

“They’re a rotten crowd,” I shouted across the lawn. “You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

I’ve always been glad I said that. It was the only compliment I ever gave him, because I disapproved of him from beginning to end. First he nodded politely, and then his face broke into that radiant and understanding smile, as if we’d been in ecstatic cahoots on that fact all the time. His gorgeous pink rag of a suit made a bright spot of colour against the white steps, and I thought of the night when I first came to his ancestral home, three months before.

What a phrase! "His glorious pink rag of a suit!" Nick is in love with the man, but can't bring himself to give the man a straightforward compliment. Even the previous compliment was really just an insult directed at the rest of society.

Lessons from The Great Gatsby

The primary lesson we can learn in dressing well from The Great Gatsby is that people will see you, at least to some extent, the way they want to see you. Tom and Nick both comment on Gatsby's suit in completely different ways. Nick sees women as masculine in the hopes that he'll eventually appreciate the way they look, and men as feminine to try to justify his feelings to himself.

This is unfortunate in that it makes it hard to represent yourself, but fortunate in that it means you don't have to worry too much about what others think... because you can't convince them of anything anyway. Dress like yourself, and the people who want to find you will find you.

In the end, the titular character's name wasn't even Gatsby. It was Gatz. He projected a superficial image of himself, people made superficial guesses, and none of them really knew what they saw.

I haven't seen any film version of the Great Gatsby, and I don't especially want to. Showing us any objective visual representation of the novel inherently defeats the study of Nick as a narrator. That said... Elevator Repair Service's Gatz is fantastic, and everybody should be forced to watch it.

Conclusion

Know yourself, and dress like that. Be authentic, but aspirational too. If you want to be seen for your ruggedness, look at workwear and denim. If you want to be seen as a bookish intellectual, go for bookcore. If you're going to wear a cap or a hoodie, consider one from your alma mater. If you want to rock a skater vibe, get Vans. If you want to look like a Republican for some reason, get the most boring khakis you can find.

But these are all simple characterizations. You're a complex person, aren't you? So combine these ideas. If you want to be seen as a fun accountant, get a gray suit, but a colorful shirt, some interesting accessory, and cool loafers from Blackstock & Webber. If you want to be seen as a future grandfather, get a cozy cardigan and some high-rise trousers, but then integrate them with who you are in the present. If you're a barber, but you want people at work to know you play tennis on your days off, wear your tennis sneakers, white socks, and maybe even a headband with your work clothes. If you want to be a cowboy college professor, take notes from Eli Cash.

Combine ideas of who you are together until your style feels distinct and personal to you. The better you understand yourself, the more complex and unique a style you will find.

And if you can't describe yourself as anybody interesting, dress as who you aspire to be. If you want to be a soccer guy, then aside from... you know, playing soccer, wear Sambas. If you want to get into art, go to a museum and get a tote bag of your favorite painting. Start baking and dressing like a dessert. If you care about your heritage, do some research and figure out the coolest aspects of your culture, and the coolest clothing traditional to it. Or just wear your grandpa's clothes. If you want to be a poser, get an Hermes belt.

You don't have to dress louder. You don't have to dress like you're in a movie, trying to commercialize your own physique. If you end up with a simple outfit, but each element represents you, and you're satisfied, that's characteristic dressing.

People will see what they want to see, but you will be comfortable in your own skin, and let them see you. Represent yourself in a thoughtful, honest way, and nothing else will matter.

Further Reading

- On Cinematic Dressing by Ethan M. Wong

- L'Ettiquette. Each issue includes detailed explanations of outfits by the men wearing them. You'll also find a sampling they call "the perfect wardrobe," and the Spring/Summer 2022 issue contains annotations by Giorgio Armani. How would you modify one of these wardrobes to fit you, and why?

- Take Ivy, with photography by Teruyoshi Hayashida. A Japanese book from 1965, Take Ivy documented the style American Ivy League students at the time, and sparked a movement of people dressing exactly like the student in the book.

- Ametora by W. David Marx, a study of Japan's fascination with "American T[o]raditional" Ivy Style.

- Black Ivy by Jason Jules, explaining the rebellious way black men reappropriated and improved Ivy style.

Podcasts

- Hand Cut Radio: Inside the Universe of F.E. Castleberry

- Blamo!: Fred Castleberry

- Style and Direction: On Cinematic Dressing (Soundcloud link)